Please note: this has been written for midwives by a midwife. If you’re pregnant – it’s worth scanning down the page as it’s full of really beneficial information. But, there is a lot of technical information and research that will mainly be of interest to professionals.

I am a practising Midwife, working at the Birth Unit at the Hospital of St. John & St. Elizabeth, a small private unit in North London. It has a” low risk” criteria for booking & delivery and our unit has international recognition for water birth and offering complimentary therapies, as well as offering traditional birthing methods, facilitating client choice (D.O.H 1993).

We currently deliver about 400 women a year and over 60% of women use the pool at some point during their labour and about 30% actually deliver in water.

Waterbirths have always been seen as normal Midwifery practise, the midwives working here have gained confidence and competence in using water for their clients, by on going support in education and by debriefing with colleagues and reflecting on practise, this has been invaluable and meets post registration education and practice (PREP) needs. We are currently taking part in a collaborative Audit of Waterbirth with other units offering Waterbirth.

I am fortunate to work with visionary Obstetricians who support and advocate water for Labour and birth and empower Midwives in normal physiology of labour, We offer Midwifery Led Care (70%) and Consultant Led Care. (30%). There is a great sense of teamwork and mutual respect; clients seek out our unit because of our philosophy of care and the option of using a pool.

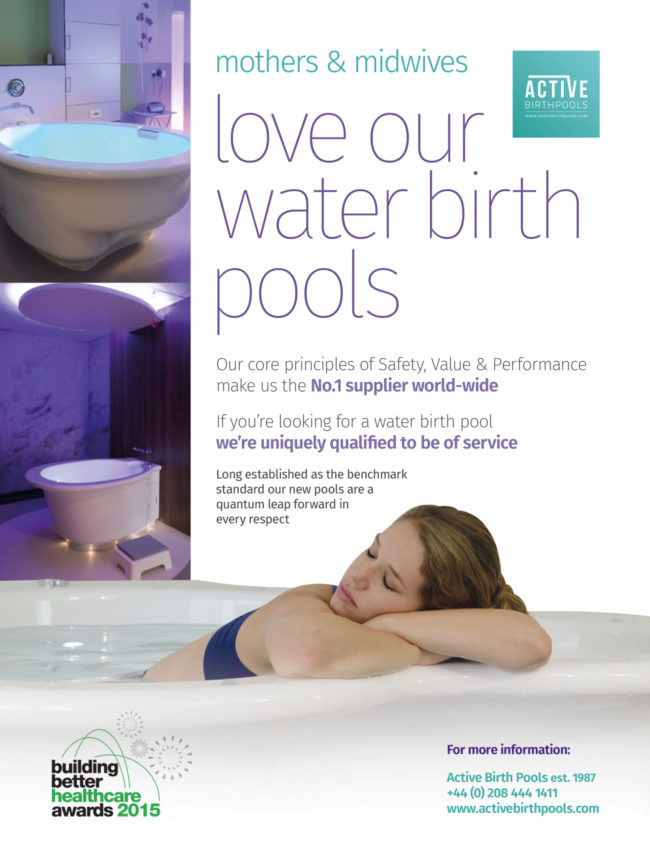

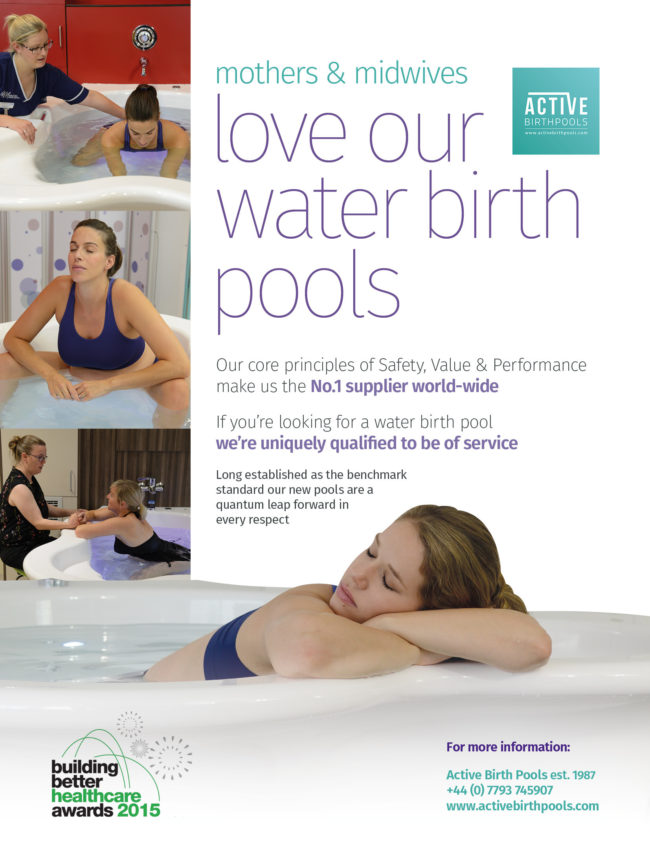

We have two pools from the Active Birth Centre and have put a lot of energy into making the birth environment as home-like as possible within a hospital setting, soft colours, dimmed lights, beanbags, birthing ball’ s, floor cushions rocking chairs and aromatherapy burners combine with the safety net of modern obstetrics should the need arise .

Water provides the midwife with an extra dimension, a great resource to enhance her skills in addition to the kind, warm, sympathetic and motherly presence that is so essential to the woman in labour.

Having met many Midwives, and many visit our unit to observe our practise and hopefully, witness a waterbirth and have the opportunity to skill- share with colleagues, there is great discord. Many are disillusioned with the Midwifery profession as a whole, such Midwives are disappointed by the cascade of interventions in their own units, having lost faith in the birthing process and the women’s ability to labour naturally.

Now, I am not saying that our unit is superior to any other, or that we only have women who only want Waterbirth and natural birth. We try to offer the optimal outcome for childbirth, if interventions are required they are very justified. We have an open, honest approach with our clients and try to address the realities of labour and birth in our classes, so whatever the outcome is a waterbirth, vacuum/forceps or caesarean section, it is hopefully a positive birth experience.

Most of what I am going to tell you is from my own 14-year experience of waterbirth, and from the evidence and research that is available, although there is still little. And a lot is anecdotal.

Many Midwives and Mother’s have enthusiastically supported the use of water in labour for birth. Many of the women I have cared for find the use of water so appealing—the soothing nature of immersion in water, the comfort of floating and moving freely, in contrast to being immobile on a bed, under bright light’s and electronically monitored. Immersion in water was popularised as a formal method of analgesia by Michele Odent in the 1970’s (Beake 1999).

It always brings a smile to the faces of women who are shown around our labour room prior to booking, they are often drawn to the pool with interest and curiosity and are keen to learn how and when we use the pool, this has an amazing effect on some women, who relax and are eager to anticipate the birth of their baby, they let go of fears so commonly inhibiting many women today, they begin to trust and some women begin to heal from previously bad birth experiences, knowing that they have a voice, good support and an environment conducive to a positive birth .

When a woman is able to labour in water, she receives positive affirmation that the birth is under her control, and that her values and her preferences are important. She is also likely to have the constant presence of a midwife whose attention is focused on her and her needs.

In 1992, the House of Commons Health Committee report on the maternity services recommended that all hospitals should provide women with “the option of a birthing pool”.

Due to lack of research on labour and birth in water at this time, the Department of health was prompted to fund a survey, so the National Perinatal Epidemiology unit (NPEU) was commissioned to undertake a survey on labour and birth in water.

219 heads of midwifery in England and Wales were sent questionnaires in 1993, the outcome was that there was no evidence to suggest that labour and birth in water should not continue to be offered as an option. Questions remained about the possible benefits and hazards and called for further research.

Labour and birth in water is now widely available throughout the National Health Service. In 1995 nearly half of all units in England & Wales were reported to have installed birthing pools.

This appears to be the case as we start the new millennium. The number of births in water in various units is still generally low; therefore exposure to this type of care for most professionals is limited. As with all aspects of midwifery care, the use of water during labour and birth requires evaluation of associated benefits and risks, yet there are no large, collaborative, randomised controlled trials to date (Nickodem, 200)

The United Kingdom Central Council (UKCC) produced a position statement on waterbirths in October 1994 recognising the need to support the Midwife and that it welcomed the recommendation those women should have choice concerning the method of delivery.

The Position paper 1a (RCM Dec 2000) clarifies the Royal college of Midwives position and recommendations for it’s members stating that all units should develop guidelines and policies on the use of water in labour and birth. supervisors of midwives should help ensure midwives acquire and sustain skills and competence and suggests midwives audit and evaluate their practise and ensure their record keeping of labour and births in water is accurate.

The council (UKCC) recognised concerns raised by Midwives, mothers and consumer groups about the potentially difficult relationships which may arise between a woman’s autonomy, a midwifes professional judgment and accountability and that of local policy in relation to waterbirths as a woman’s chosen method for the delivery of her baby.

Midwives need the support from their Supervisor of Midwives when faced with such dilemmas. .Supervision was written into the MIDWIVES Act 1902 and has remained a statutory requirement until this day. The Supervisor of midwives is responsible for maintaining identifiable objectives, setting standards, ensuring competent practice, supporting staff and identifying training needs as well as fostering a supportive environment for birth and supporting change..

She is an advocate for clients and a supporter of Midwives , supporting women in their choice of care, and Midwives providing that care, She is a resource for learning material and experience, encouraging on going education.

Consequently schools of midwifery and study days/workshops were introduced to offer sessions on labour and birth in water for midwives offering the opportunity to discuss practical and clinical issues thus helping midwives to acquire new skills and update themselves .I am continually surprised at how much I continue to learn despite my many years of experience of waterbirth. This facilitates PREP’s statement of lifelong learning.

Birth in water is considered a “normal birth” and as such midwives have a responsibility to reflect and re-visit their Midwives Rules and The Midwives code of practise (UKCC 1998)The code is very clear that we ensure we are competent in skills acquired in our training and after registration and in maintaining those skills and that as a midwife we are accountable for our own practise in whatever environment we are practising.

Rule 40 : The responsibility and sphere of practise (UKCC 1998)

It is the wording of this rule that both enables the Midwife’s autonomy and at the same time delineates its boundaries.

It states:-

1. A practising Midwife is responsible for providing Midwifery care to a mother and baby during the antenatal, intranatal and postnatal periods.

2. Except in an emergency, a practising midwife shall not provide any midwifery care, or undertake any treatment, which she has not, either before or after registration as a midwife, been trained to give, or which is outside her current sphere of practise.

3. In an emergency, or where a deviation from the norm, which is outside her current sphere of practise, becomes apparent in the mother or baby during the antenatal , internatal or postnatal periods, a practising midwife shall call a registered medical practioner.

REFERENCES:

Maxwell B Water & Birth- Legal Implications Hunter Valley Midwives Association June 1997 vol 5 no 3

Keane H. the Waterbirth Experience, A Supervisors Perspective January 1995

Street D Waterbirths; Client Choice versus legal implications Nursing Times November % 1997 vol 93 no 45

United Kingdom Central Council position statement on waterbirths 1994

Royal College of Midwives Position Paper The use of water during birth July 1994

I have tried to address the most commonly asked questions that midwives ask and are concerned about regarding labouring and giving birth in water .I have included some practical tips from my own experience.

I would like to stress that the midwives clinical judgment, intuition and common sense is paramount.

Q. WHAT SHOULD THE TEMPERATURE OF THE WATER BE IN THE FIRST STAGE AND SECOND

STAGE OF LABOUR?

A. Labour 32°c- 36°c

Birth 36°c- 37°c

Measure hourly & record in the mother’s records. Record temperature in second stage. Bath thermometers are inexpensive to buy and can be cleaned following individual use.

This range of temperature is said to enhance uterine activity and prevent the baby from initiating respirations.REF:- Catherine Charles. BJM March 1998, vol 6, No 3.

O’dent Michelle, The Lancet. December 1983, pg 1476-1477

Johnson. P birth under water: To breathe or not to breathe J Obstet Gynaecol 1996

Q. WHAT IS THE RECOMMENDED TIME TO ENTER THE POOL?A It is recommended that the ideal time to enter the pool is when labour is well established and the cervical dilatation is 5cms or more. Getting into the pool too early may slow the process down. But if this should happen then leaving the pool & adopting upright positions will help.

However, I feel a degree of flexibility is required, and women reviewed individually, for some women having an intense labour experience, it may benefit from entering the pool earlier. In some cases I have known this has been of benefit and the woman has relaxed enough to “let go” and surrender to the birth process and has consequently made good progress.

I am amazed to witness the effect water can have on some women, from not coping “on land” to total submission, often the sound of “Ahhhh”! is heard as the woman steps into the pool, this has a wonderful effect on everyone!

REF:_ Odent M Use of water during labour- updated recommendations. MIDIRS, Midwifery Digest, March 1998, vol 8, No 1, Pg 68-69.

Odent M can water immersion stop labour? Journal of Nurse- Midwifery, vol 42, No 5 Sep/Oct 1997 pg 414-416

Eriksson, M Mattsson, L-A, Ladfors, L, Early or Late bath during the first stage of labour a randomised study of 2O0 women, Midwifery, vol 13, No 3 September 1997. Pg 146-148.

Boulvain M & Wesel S Neurobiochemistry of immersion in warm water during labour: The secretion of Endorphins, cortisol and prolactin.

Q. WHEN TO LEAVE THE WATER?

A I think here the midwife needs to review the nature of the labour and any risk factors .If in doubt get the mother out!

In my experience women will be asked to leave the pool for the following reasons:-

- Concern over the condition of the baby, changes in the fetal heart or meconium stained liquor

- When there is failure to progress in labour first or second stage.

- In second stage , when a large for dates baby is suspected to birth on land

- If the water becomes heavily soiled

- Maternal request, when further analgesia is required.

- In 3rd stage if there is excessive blood loss .or where there is a low haemoglobin estimation and the need for active management of 3rd stage.

Q DOES THE MIDWIFE GET INTO THE TUB?A No, with carefully designed pools, providing good access this is not necessary, apparently Michel Odent stepped into the pool in his socks, when his first waterbirth took him by surprise!:

In my experience I have never known it.

TIP. Midwives attending a waterbirth are best to wear light cotton trousers and top that can easily be changed should they get wet. Birth attendants are easily able to touch, massage and assist the mother in the pool.

Water spillage can occur as the woman steps out of the pool, or leans over the pool, try to clear up any water as soon as possible to prevent slippage, I usually have a towel or floor mat near by. A non-slip bathmat is also a good idea.

Q. HOW OFTEN SHOULD THE FETAL HEART BE MONITORED?

Prior to entering the pool the fetal heart will have been monitored and found to be normal, depending where the labour is taking place i.e. home or Hospital. Unit protocols should be followed.

In my unit a cardiotocograph (CTG) will have been performed on admission and repeated 4-6 hourly unless a deviation from the norm is detected.

Everyone with a portable acqua dopper sonic-aid devise can hear fetal heart tones.

In order to exclude fetal heart decelerations it is important to listen to the fetal heart immediately at the end of a contraction and from time to time during a contraction.

During the first stage of labour every 30 mins

During second stage of labour after every contraction or every other one.

Follow your instincts, if any concern asks the woman to leave the pool and commence continuous fetal heart monitoring.

All observations and events should be clearly recorded in the mother’s records, this is an integral part of midwifery practise.Q. WHAT IS THE H:I:V: RISK RELATED TO WATERBIRTH?

A. H.I.V is a very fastidious virus, meaning that it has a very hard time surviving outside of its preferred environment. It is thought that the water would provide a barrier to transmission due to the dilution effect of the water.

It is becoming increasingly more routine to offer antenatal H.I.V. screening of women

Some NHS trusts have denied women access to use the pool until screening tests showed they were H.I.V. negative, this is certainly controversial.

However birth attendants should adhere to universal precautions. ( Guidelines have been issued about universal precautions for the protection of health-care workers (D.O:H. 1990)

Wearing gloves is essential:_

TIP

- I advice wearing a half size smaller to provide a watertight fit

- Gauntlets are available, but my colleagues and I do not find them to be very user friendly! The latex is rather thick..

- I have known Midwives to cut off the fingertips of the gauntlets and wear them over regular gloves for better protection.

- Obviously cuts and abrasions on the hands should be covered with suitable plasters.

- Keep hands out of the water as much as is possible a “minimal touch” delivery technique is advocated.

REF:- Garland D, Jones K Updating the evidence BMJ June 1997 Vol 5, No 6.

No hepatitis or HIV test, no waterbirth Modern Midwife October 1995

Harley J. The use of water during labour & Birth. RCM Dec 1998, Vol 1, No 12.

Tedder, Prof R.S, Ridgeway, Dr G Blood-borne viruses, Labouring pools and birthing pools January 1996

Q. WHAT OBSERVATIONS ARE REQUIRED?

Observations as per normal practise of maternal temperature, pulse and blood pressure should be done prior to

Entering the pool and can easily be performed in the pool.

The use of the new GENIUS ear thermometers make’s life much easier. Monitoring maternal temperature ensures

That she is not over or under heated.

If there is a concern with the blood pressure it can be recorded in between a contraction with the mother either

Kneeling over the rim of the pool or sitting on the rim of the pool supported.

I have seen blood pressures lower due to the benefits of the mother relaxing in the water; this can be very helpful for

The woman who has mild hypertension.

Listening and observing the woman are very important skills that the midwife should follow.

WHAT ABOUT VAGINAL EXAMINATIONS?

Vaginal examination can easily be performed in the water with the mother lying, kneeling or squatting, supported by her partner. If a proper assessment is needed then the woman should be asked to leave the pool. In my practise I have found that the need to perform vaginal examinations in water is less. Evidence suggests that most women will deliver, for primigravida 4-5 hours, for multips 2-3 hours.

I have always found women to be co-operative and eager to please and will move, change position to help if it is necessary.

If the woman is deep in the water, I have found my examination not to be so accurate and depending on what the indication for examination may request that she leaves the pool.

REF. Warren C Why should I do vaginal examinations? The Practising Midwife June 1999 vol 2, No 6 pg 12-13

Q. HOW DO YOU CONDUCT THE 2nd STAGE OF LABOUR IN THE WATER?

The emphasis should be on the normal mechanism of labour.

Midwives will need to adapt their practise and technique to the position the mother adopts.

Equipment required and useful for a waterbirth’-

- Warm towels, for mother & baby

- Large sanitary towel

- A bath robe

- A delivery pack & cord clamp, sterile gloves

- Mirror

- TorchSieve/bucket/fish net needed to sift out any debris

- Bath thermometer

- Non-slip bath mat

- Water to drink for everyone

- Evian spray & lip salve

- Waterproof sonic-aid.

- Resuscitation equipment checked and near by.

- Syntometrine or syntocinon at hand should it be needed.

- Call bell that is easily reached, ours are fixed over the pool or emergency numbers if at home.

- A low stool, birth ball beside the pool for midwife and partner.

Never leave the woman alone. It is important to remind the mother of the importance of keeping her bottom under the water during delivery

Many units advocate the presence of a second midwife at the time of delivery this is helpful not only for practical reasons, but also an opportunity for midwives to skill-share and observe a waterbirth.

Check the temperature of the water it should be 36-37°c

It is very easy to observe progress; some suggestions may be required if pushing is ineffective. changing position, more upright to aid gravity.

Be prepared for the unexpected! I have known women to stand up out of the water at the last moment, if the baby’s head is delivered above the surface of the water then the delivery is conducted out of the water until full expulsion, then she can sit down into the water with her baby.

A part from the face, keep the baby immersed in the water to ensure that body temperature is maintained.

Michele Odent (1984) noted that women spontaneously leave the pool in second stage to birth their babies, whatever their previous intention had been.

If second stage progress is slow then leaving the pool, so the woman can maximise her pushing power is recommended.

Delivery of the head is technically a “hands off” procedure; this is achieved when there is a good rapport between woman and midwife. A mirror is useful to help see the advance of the baby’s head also I have found some women and partners like to see and this encourages them to progress further. .

The head may crown in full view, alternatively the midwife may use her hand to gently feel the advance of the head, this can be helpful, not to “guard the perineum” as in traditional birthing, but in order to determine if maternal efforts need to be gentler, and not so forceful to minimise perineal trauma and give some direction. The midwife will know if this is necessary.

Minimal intervention is needed, there should be no hurry, when the baby’s head is born, wait for the next contraction, I remember with the first few waterbirths I assisted finding myself holding my breathe! Being anxious and keen to deliver the baby up to the surface of the water, 2-3 minutes can pass, so remain calm!!

The baby is born completely under water and in a slow gentle movement brought to the surface, a movement that will generally take between 5-7 seconds.

The baby’s well being should be monitored throughout and ascultating the fetal heart immediately after a contraction will ensure you detect any late decelerations, if any concern the woman is asked to leave the pool.

I have seen baby’s open their eyes under water.

Usually the baby is handed directly to the mother, but be prepared, as I have had occasions when the mother has needed a few minutes before receiving her baby.

Checking the umbilical cord for pulsation reaffirms that the baby is still receiving oxygen via the placenta; this gives a good indication of the baby’s condition. Often water babies do not cry and are very peaceful so feeling the cord is reassuring.

Q WHAT IF THE CORD IS TIGHT AROUND THE NECK?

It is not necessary to feel for the cord prior to the birth of the shoulders, once the head is born. Feeling for the cord causes discomfort for the mother. If the cord is around the baby it is simple to rotate the baby’s body under the water to disentangle the cord. If the cord is so tight that it might adversely affect the baby late decelerations will be obvious and the woman will be asked to leave the pool.

NEVER CLAMP & CUT THE UMBILICAL CORD UNDER WATER. This is risky and time-consuming sine it could trigger respiration or stimulate the baby. If the cord was that tight you would of detected decelerations of the fetal heart rate prior to delivery.

Q WHAT ABOUT THE RISK OF THE CORD SNAPPING?

This is very rare, but some cases have been reported.

Delivering the baby gently to the surface of the water and avoiding being to hasty will help prevent excessive tension on the cord.

These suggestions may help. –

- Ensure that the water is not unnecessarily deep.

- Have cord clamps ready

- Deliver baby gently and away from the mother, it is then possible to view length of cord

- If any concern or for a short cord, pull the plug or ask the mother to lift herself up

REF: -Gilbert R E. Tookey P A Perinatal mortality & Morbidity among babies delivered in water: surveillance study

And postal survey B M J 1999, 319 483-7.

Anderson Tricia Practising Midwife Umbilical cords & underwater birth. The practising Midwife February 2000 vol 3 no 3 no 2 p12

ESTIMATING BLOOD LOSS IN WATER?

The amount of blood lost during and after delivery is difficult to estimate in the water, due to the dilution effect of the water.

With experience, midwives become better at gauging this, but if bleeding seems excessive then the woman should be helped to leave the pool.

Observing the mother will make you aware of any ill effects. If a mother feels faint she should leave the pool or the water should be drained

It has become common to estimate blood loss as less than or greater than 500mls. In my experience, I am surprised how often the water is clear following the birth, usually due to little perineal trauma.

Midwives must follow their intuition and gut feeling on this, if in doubt get the woman out!

Use a sieve or fish net to collect any blood clots.

In the case of a post partum haemorrhage I would suggest the following will need to be done;

- Pull the plug, call for help

- Administer syntometrine intramuscular

- Help the mother out of the pool to lie down either on a floor mat or on the bed if it is close ask the partner/colleagues to help you

- Wrap in warm towels or robe and rub up a contraction.

- Deliver the placenta if not delivered

- Estimate the blood loss

- Site an intravenous infusion if required and take blood for x-matching

- A syntocinon infusion may be requested

- Check the bladder is empty

- Record observations of maternal pulse & blood pressure and observe maternal condition

FAINTING

Should a mother feel faint while in the pool it may be best that she leaves the pool, the room often gets heated up with the vapour from the water, perhaps she has overheated. practical suggestions like opening a window, the use of a fan, drinking cold water or tepid sponging may help, and getting her to breathe slowly. Check her pulse and blood pressure. A glucose sweet or energy drink may also help. Rescue remedy and homeopathic arnica are useful.

IS IT SAFE TO DELIVER THE PLACENTA IN THE WATER?Yes, in the absence of complications the mother may remain in the water. A physiological third stage of labour is conducted unless there are contra indication e.g. low haemoglobin estimation.

Always have syntometrine available.

Unit to unit policies will differ on this, but in my own unit we wait for the umbilical cord to cease pulsating prior to clamping and cutting the cord, unless there is a concern. Sometimes the placenta is delivered prior to the baby being separated. Michel Odent (1993) suggests that the umbilical cord should be cut 4-5 minutes after the birth to reduce the risk of polycythemia.

In my experience, if you ask the woman to bear down with the next contraction she feels the placenta is often expelled with ease. Using upright positions assists gravity.

Remember “hands off” and no fiddling with the cord as this can cause undue bleeding.

The third stage can average 20-40 minutes. I have known it to take longer and leaving the pool is advisable, often this helps and the placenta is birthed easily.

In the absence of bleeding and if the mothers condition is satisfactory, be patient, putting the baby to the breast obviously will help.

Giving a homeopathic remedy like Arnica or pulsitilla in a 200-potency ca help.

TIP Have warm towels available and a large sanitary towel. As well as a bowl to catch the placenta.

In my own experience I have found mothers quite keen to leave the pool if the placenta is slow to be birthed.

Fathers are asked if they would like to cut the cord as a symbolic gesture. Often the Dads can enjoy their first cuddle with their baby while the placenta is being delivered.

WHAT IS THE CONCERN REGARDING WATER EMBOLISM?

This is a theoretical risk of introducing water into the uterus as the placenta is delivered, in theory allowing water to enter the mother’s bloodstream through the blood vessels at the placental site.

Back in 1993 Michel Odent raised the question of water entering the vagina and uterine cavity if the placenta is delivered while the woman was still in the water. Since that time many water births have occurred and many placentae have been born into water, without any incidence of water embolism.

In reality, immediately after birth, the vaginal walls touch one another, even if there was a tear so that the vagina is a potential cavity rather than an actual one. So it is extremely unlikely to happen.HOW DOES THE BABY BREATHE?

It is commonly believed that the stimulus to breathe is from the baby’s face coming into direct contact with the cool air and this only occurs when the baby is brought to the surface of the water.

This is one of the main concerns that I hear Midwives and parents expressing about the possibility of the baby inhaling water at the moment of birth.

When the head emerges underwater the chest is in the mother’s pelvis and water cannot be inhaled because the lungs do not expand. The baby continues to receive oxygen via the umbilical cord, therefore the umbilical cord SHOULD NOT BE CUT prior to full expulsion and birth of the baby.

It is important to instruct the mother to keep her bottom under water during delivery, if for some reason the mother lifts herself up and this does happen, then the delivery is conducted above the surface of the water.

Dr Paul Johnson’s work “Birth under water”-“To breathe or not to breathe” (1995) concludes that if the onset of labour is spontaneous, no drugs are administered a baby born with it’s cord in tact, into warm water not asphyxiated,

Is inhibited from breathing. Surfacing into cooler, dryer air provides the stimulus for the baby to start to breathe.

Therefore it is important to detect fetal heart decelerations, particularly late decelerations and hypoxic babies as hypoxia inhibits breathing in the fetus, except if very severe, when gasping occurs.

The entrance to the larynx is bristling with chemoreceptors, water in the larynx causes the diving response.

REF: Johnson P Birth under water- to breathe or not to breathe British Journal of Obstetrics % Gynaecology, vol 103, no 3 March 1996 pg202-208

Letter Birth under water- To breathe or not to breathe, MIDIRS Midwifery Digest (Jun 1997) 7:2 pg 201

Eldering G, Selke, K Water birth- A possible mode of delivery? Waterbirth Unplugged books for midwives Press 1996

WHAT ABOUT THE PERINEUM?

Technically conducting a waterbirth is a “hands off procedure”

Water softens the tissues and allows it to stretch so those deep tears are very uncommon under water.

I believe in a slow gentle delivery of the head using the maternal breath, obviously some women need more guidance than others, this is where having continuity of carer, building a relationship between client and professional, having trust all helps.

Visibility will depend on what position the mother chooses to use, the use of a mirror and torch will help if the mother is squatting or kneeing.

I have never performed an episiotomy in the water, but I have known colleagues who have, with the mother floating supported in the water. In my unit we do not advocate performing episiotomy in the water.

For occasions when the head is crowning for longer than usual, just changing position to being more upright or to even stand up has aided delivery and gravity.

SUTURING Often after a waterbirth if sutures are required it is best to wait an hour before inserting them as often the perineum is water logged, in reality an hour passes fairly quickly.

SHOULDER DYSTOCIA & WATERBIRTH

This is an avoidable tragedy and the detection of risk factors prior to birth would warrant a land birth.

RISK FACTORS: – Exclusion for birth in water

Large for dates baby

Poor progress in first stage, early second stage of labour

Previous history.

Midwives “gut feeling”

This is an emergency situation and medical aid should be called. In the event of the shoulders being difficult to deliver, the midwife will call for help and I would pull the plug and help get the mother out of the pool, just the movement of standing up or lifting her leg over the edge of the pool as getting out could be enough to deliver the baby, she will need help to physically do this, enrol her partner & colleagues.

Then adopt a supported squat position or MRoberts position, lean mother onto a beanbag for support.

Apply supra-pubic pressure; follow your unit’s protocol.

Shoulder dystocia drills are recommended as good practice for staff to feel competent and confident in dealing with this emergency situation, we cover the “what if” situation related to waterbirth in our play stations.

Remember record keeping relating to shoulder dystocia is very important.

E.g.

Not time of perineal phase of the second stage of labour

Note first indication of the shoulder dystocia

Note sequence of events i.e. 1st attempt at delivery

Episiotomy attempted or reasons for not performing

Positions used to facilitate delivery

Manoeuvres used to facilitate delivery

Note time between delivery of the head and the completion of the delivery of the

Baby.

Details of any resuscitation if required.

TWINS & WATERBIRTH

This is usually contra-indicated and stated in unit protocols and guidelines, however there are reports of twin births in water I have actually delivered twins in water but it was not planned, this was a muligravid mother who had a quick, easy delivery of the first twin in water, she left the pool for the second twin as we thought it to be a breech presentation, but actually after an examination it was a head presenting, all was normal, the mother asked to get back into the pool, there was no reason why she should not and with the next two contractions her second twin was born .I had the support of the attending obstetrician.

HOW DOES THE MIDWIFE LOOK AFTER HER BACK?

The health and wellbeing of midwives is very important. In the National Survey on waterbirths (1995), out of 8255 reports of women using water in labour, seven members of staff were reported to have suffered back problems. It is recommended that each Midwife attends an annual moving and handling course and must adhere to the recommendations.

I try not to lean over the pool, I usually pull a stool or chair next to the pool or sit on a birth ball or kneel at the side of the pool. Leaning over the pool unnecessarily is hard on your back. so keep bending over the pool to a minimum and wipe up any excess/spilt water from the floor to prevent falls/slipping.

We do manual handling sessions related to caring for clients in the pool, to look at ways of being kinder to ourselves and taking care of our backs and posture.

Make sure your knees are bent and try to be more conscious of your posture when leaning over the pool.

With care and good postural habit, stress on the spine can almost be avoided. Keeping fit and supple with simple yoga based exercises can help

If you have a back problem or a concern you should discuss this with your manager and occupational health department.

SUGGESTED READING: –

RCM 1999 Handle with cares, a midwives guide to preventing back injury.

RCM 1998 health & Safety representatives handbookRECORD KEEPING

“Record keeping is an integral part of nursing, midwifery and health visiting practise. It is a tool of professional practice and one which should help the care process” (UKCC 1998 Guidelines for records and record keeping).

Good record keeping is paramount and a mark of the skilled and safe practitioner (UKCC 1998)

- Keep accurate, consistent notes and write events as soon as possible after an event, providing current information on the care and condition of the client

- Write clearly in black ink

- Accurately dated, timed and signed with your signature printed along side the first entry

- In relation to waterbirth, record temperature of water, time of entering , leaving the pool and mother’s and baby’s condition

- Record any discussions or plans of care that takes place with the involvement of the client.GUIDELINES FOR THE USE OF WATER IN LABOUR.

For the first time, guidelines have been produced on the best available evidence for good practice when assisting with labour and birth in water, for use in hospital or home.

The guidelines are intended to reinforce good midwifery practice, and to suggest ways in which a midwife can best, and most safely support a woman who labours and may give birth in water. (Burns E & Kitzinger S Midwifery Guidelines for use of water in labour 2000 )

Each unit will have a guideline/protocol and criteria for Midwives to follow related to the use of water for labour and birth.

Here is an example of our own guideline: -CRITERIA FOR USE OF WATER IN LABOUR

- An uncomplicated pregnancy of at least 37 weeks gestation.

- Established labour- preferably when the cervix is greater than 4cms dilated( contractions usually peak within two

Hours of entering the pool therefore entering the pool too early may slow down the labour).

- No specific indication for continuous monitoring of labour

- The mother must be attended by midwife/labour partner at all times and must be aware that she will be requested

To leave the pool should complications arise, two midwives must be in attendance during the birth of the baby.

WOMEN SHOULD BE URGED TO LEAVE THE POOL IF:

- Excessive fear, anxiety or loss of control exists

- There is significant blood loss at any time

- Augmentation with syntocinon is required.

- If there are significant abnormal changes in the fettle heart rate

- If moderate to thick meconium stained liquor is present

- If the contractions stop or significantly slow down

- If there is lack of progress after pushing for greater than an hour in the second stage

- If the woman has an abnormal rise in blood pressure

- If assistance is needed to deliver the head or the shoulders(help the mother to stand up for the first attempt to deliver to be made)